Teju Cole declares his intention in Open City was to write a la Cartier-Bresson — “on the run” — and urges others to do the same.

What does this entail?

Henri Cartier-Bresson said photography is not like painting. It requires both seeing “a composition or expression that life itself offers you” in a flash, and acting “in that creative fraction of a second”. [1] In painting, by contrast, more time and labor are needed to fashion an object with comparable expressive content.

John Berger characterizes the difference between the process involved in producing a photograph and the process involved in painting as that of “quoting” versus “translating”, “receiving” versus “making”. The photograph requires both a mediated choice, which is a cultural construction, and an immediate, natural, and unconstructed trace produced by the particular configuration of light entering the camera. The photographer “quotes” from appearances that lie in front of the camera. The photograph is a quotation based on the photographer’s instantaneous judgment. A painting or drawing, on the other hand, is the result “of countless judgments…. [E]verything about it has been mediated by consciousness, either intuitively or systematically”.*

And what about writing? How does an attentive writer capture a moment “that life itself offers”? Is it not a long step away from producing a photograph, different in kind from a photographic image? How can we compare them?

If we go back to the passage (in the previous post) from Berger’s essay — gazing onto the courtyard from a window far above — maybe we can find an answer.

Berger sets the scene in a long picture gallery with tall windows overlooking a sunlit courtyard two stories below. We can imagine a few people, perhaps some children playing down below. Then, suddenly, the perspective shifts to a reverse view from below looking back at Berger, a “vision” of the narrator “alone and stiff in his window”. A “chiasm” emerges — a reflexive relation. The narrator says, “I see myself as seen. I experience a moment of familiar panic.”

Click. The image is captured, the text cuts as the narrator turns back to the framed images in the gallery.

The reader is left with an image and several questions. What is the function of this image in Berger’s story? Will the image come again? With what effect, what meaning? What light will it shed on what we’ve read?

So there may be a way of simulating an “image on the run” in writing. Its value would be poetic. We anticipate connections that do not immediately appear, we look for them. If they don’t show up, we create them.

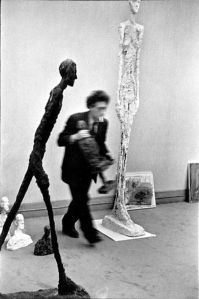

But notice the difference in our expectations when we’re looking at photographs. In a photograph by Cartier-Bresson, for example, something is immediately given — a fuzzy-haired man in a dark suit and tie holding a small sculpture walks briskly between two similar but much taller figures. The image, half again as high as it is wide, captures a moment. In what appears to be a relatively empty room containing several other artworks — busts of human heads on the floor and several small paintings or drawings resting against the wall — the man is moving objects around. To what end? Is he in a museum, an art gallery, a studio? Is he the artist, a curator, a dealer? When did this occur?

When a scene such as this is described in a novel or a short story, we assume the answers will eventually be given. No such assumption arises when looking at photographs. Very often the only additional source of information is the title, the name of the photographer, and the year the photo was taken. If it is part of a larger suite of related images in a book or magazine, the context may provide additional background information.

But when it is taken out of its original context and placed, as it was in this case, in a Wikipedia article on Cartier-Bresson which I came across this morning, I’m given no date, only the image labeled “Photograph of Alberto Giacometti by Henri Cartier-Bresson”. Looking up the image in an exhibition catalog**, I see that it was, in fact, one of seven photographs that appeared in a British magazine under the title “A Touch of Greatness: Giacometti”. The catalog places the image in Cartier-Bresson’s oeuvre, but provides very little on the photograph itself — taken in 1962 as the artist installs an exhibition of his work. I’m given information about the object. But I create whatever meaning and expressive content I can get from looking at the object. I contribute in this way, looking from a distance — a distance the image itself may shorten, but never eliminate.

———————————-

*John Berger and Jean Mohr, Another Way of Telling, New York: Pantheon, 1982, 93.

** Peter Galassi, Henri Cartier-Bresson: the Modern Century, London: Thames & Hudson, 2010.