I was in Letterkenny in June and made a point of visiting the Donegal Regional Cultural Center (RCC).

I was in Letterkenny in June and made a point of visiting the Donegal Regional Cultural Center (RCC).

The center, designed by MacGabhann Architects, a longstanding Letterkenny firm, has been praised by critics for its clarity of design, sculptural presence, and the collaborative process throughout its development and construction.

[See “A Beacon for Donegal”, Marianne O’Kane Boal, Irish Arts Review, 24 #4 (Winter 2007).]

While talking with one of the staff members, I noticed a small display of publications on a rack next to the front desk, which included several copies of OPEN e v+ a 2007 — a sense of place, a catalog from the e v+ a 2007 group exhibition in Limerick.

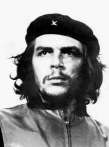

One work in the catalog that caught my eye was CHE (2007), by Sean Lynch, which includes a reproduction of Alberto Korda‘s photograph of the Cuban revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara —  Guerrillero Heroico (Heroic Guerrilla) — taken at the memorial service in the wake of the La Coubre munitions explosion in Havana harbor in 1960, which killed over a hundred Cubans.

Guerrillero Heroico (Heroic Guerrilla) — taken at the memorial service in the wake of the La Coubre munitions explosion in Havana harbor in 1960, which killed over a hundred Cubans.

The very appearance of this classic image of Che in an art catalog inevitably appears as a cliché given its widespread dissemination on…well, you name it — posters, films, books, magazines, t-shirts, bustiers, scarves, watches, tissues, pesos (paper and metal coins), coffee mugs, dolls, cigarette packages, lighters, and papers, ice cream wrappers, vodka adverts, maracas, mouse pads, etc., etc., etc. “[It’s] considered the most reproduced image in the history of photography”, according to Trisha Ziff, curator of the 2005 exhibition, Revolution and Commerce: The Legacy of Korda’s Portrait of Che Guevara, organized by UCR/California Museum of Photography. (This past spring Ziff’s film, Chevolution, was screened at the Tribeca Film Festival.

In the e v+ a catalog, Lynch’s framed image of Che is accompanied by another reproduction, this one of a newspaper article, along with the following contextual information provided by the artist.

A brief article appeared in the Limerick Leader on 15th March 1965. Written by Arthur Quinlan, it describes the visit of Che Guevara to Shannon Airport and Limerick. Guevara stayed and drank at Hanratty’s Hotel in Limerick. Its residents’ bar was nicknamed the Glue Pot. The previous weekend, at a conference in Algiers, Guevara denounced the Soviet Union for failing revolutionaries across the globe. As he drank in Limerick, he know that his return to Cuba would be a difficult one, since Fidel Castro was a close ally of the Soviets. When back in Cuba, he informed Castro of his intention to become a roaming revolutionary, and then left for the Congo. Quinlan was the last journalist to interview him. Guevara was killed in Bolivia two years later. (Incidentally, Guevara and I are related. His grandmother shared my surname, Lynch, and we both originate from 17th-century Galway.)

Jim Fitzpatrick, the Irish graphic artist responsible for wide dissemination of the image in Europe, claims to have seen Che while working in a bar as a young man. Che, according to Fitzpatrick, was passing through Ireland on his way to Moscow.

I came across an article about the iconic image of Che on the BBC website. The author quotes Fitzpatrick, but does not give the location of the bar. I wondered if, perhaps, it was at the Shannon airport or Hanratty’s in 1965, Kilpatrick’s recollection being a few years off the mark. Then, in a recent interview with Fitzpatrick by the artist Aleksandra Mir, I found a more extended account of the meeting in which he says the bar was located in a hotel in the seaside town of Kilkee.

(Incidentally, Arthur Quinlan’s more recent recollection of his 1965 meeting with Che Guevara is archived on the website of the Society for Irish Latin American Studies (SILAS). And writer Martin Hannan’s article about Che, with a focus on his interview with Quinlan, is also informative.)

I found the story of Che’s links to Ireland a little surprising, but didn’t think much more about it while in Letterkenny. We were heading off the next day to a cottage on the Isle of Doagh and I was drawn more by the lure of sea, sheep, and rocks than with archives and revolutionaries.

I found the story of Che’s links to Ireland a little surprising, but didn’t think much more about it while in Letterkenny. We were heading off the next day to a cottage on the Isle of Doagh and I was drawn more by the lure of sea, sheep, and rocks than with archives and revolutionaries.

I was back in Dublin about a week later and spent an afternoon at the Irish Museum of Modern Art. In one of the temporary exhibition galleries, I found an intriguing and somewhat enigmatic suite of photographs. The piece, it turns out, was about the artist’s search for a lost bicycle linked to Flann O’Brien and his well-known novel, The Third Policeman, which I’d been reading back in New York. The artist was Sean Lynch.

Now it also happens that I’ve been working on a project having to do with the absence of contextual material in contemporary art and was struck by the fact that this particular work, as well as the Che piece, seemed to buck the rather prevalent tendency in conceptual-oriented photographic practice to put the “burden of contextualization” on the viewer. Lynch was, in fact, providing the backstory for CHE and, in the work installed at the IMMA, incorporating both a newspaper excerpt relating a tale about O’Brien’s “lost bicycle”, as well as a follow up letter from the artist describing his failed attempt to locate the bike. I made some notes and wandered on through the rest of the exhibition.

Later that afternoon I came across a small display adjacent to the main entrance. The IMMA has an “artists’ residency programme“, which provides studio space on the premises. I discovered this program several years ago on my first trip to Dublin and, visiting one of the artist’s studios, learned about the Burren and Kilmainham Gaol, which is a short walk from the museum.

The display listed participating artists along with short bios and descriptions of their work. One of the artists currently in residence was Sean Lynch. The next morning, just before catching my flight back to America, I decided to look him up. By coincidence, we crossed paths in the museum lobby and had a lovely and very informative discussion in his studio.

Sean was very generous with his time, showing me a number of recent projects, while I relentlessly pursued the question of “the mute object”. I explained that I was thinking, in particular, about artists such as Christopher Williams, Simon Starling, and others who draw on a rich set of historical events linked politically, socially, culturally, or economically to the objects they exhibit, but not necessarily referred to directly in the presentation of the work. They demand an active and curious viewer willing to engage with the work by finding or reconstructing a larger and relevant context.

So, given Sean’s research-based practice, which links him to these other artists, I was interested in his rationale for providing info on the backstory as part of the installation of his work, rather than taking the Williams/Starling approach and leaving it to viewer to puzzle it out through their own initiative. More on that later…